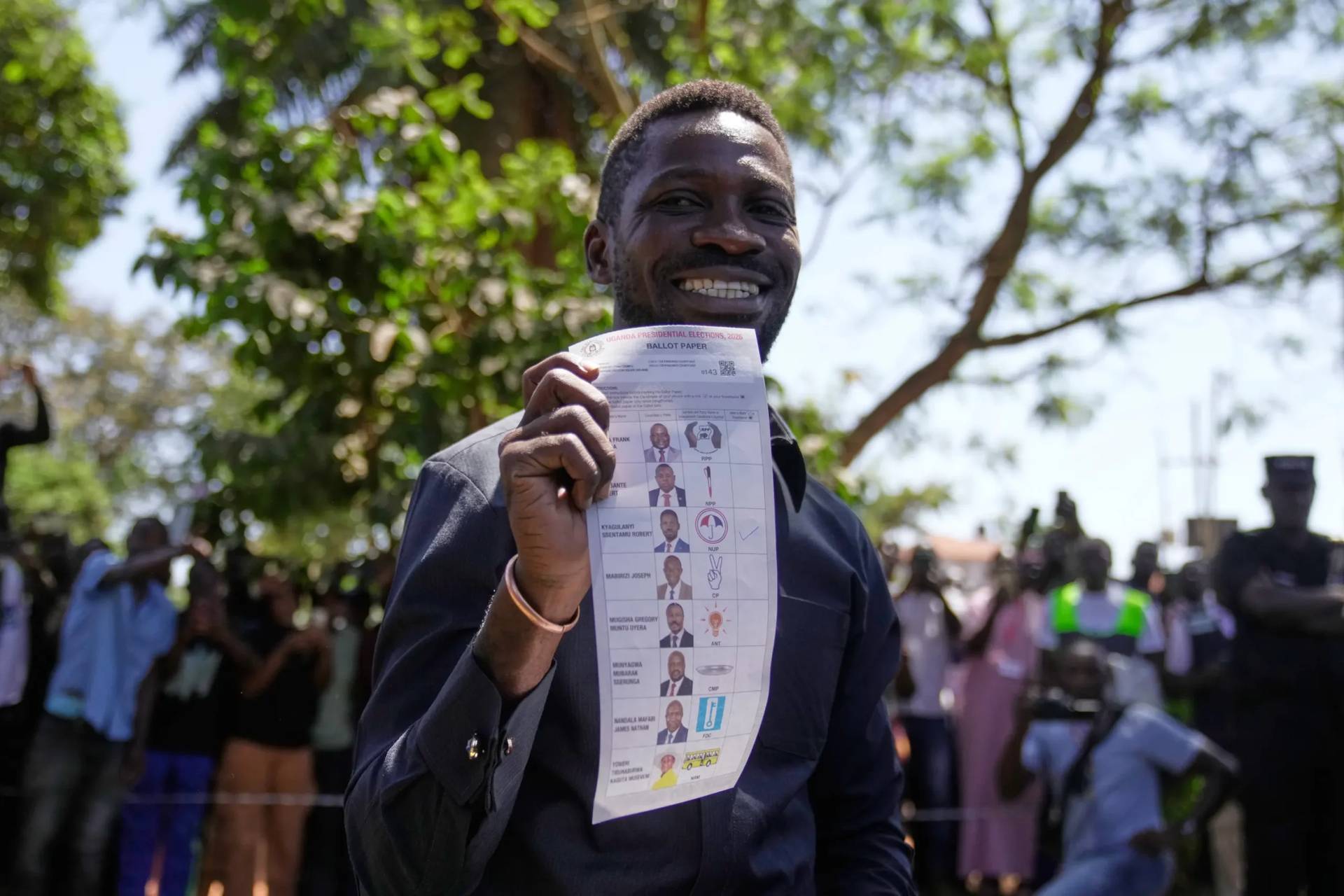

With the election of center-right President Rodrigo Paz on Oct. 19, the Bolivian Church may regain a special place among the South American country’s religious institutions, after almost 20 years of socialist administrations.

Paz, whose family includes a number of former presidents and top Bolivian authorities – like his father, Jaime Paz Zamora, who ruled the country between 1989-1993 – is expected to restore the traditional role the Church has historically enjoyed, giving it more visibility than it had under the administrations of former President Evo Morales’s Movimiento al Socialismo (movement towards socialism, also known by the Spanish acronym MAS).

Morales ruled the nation between 2006-2019. His successor, Luis Arce, took office in 2020 and will step down next month.

Bolivian clergy, to a great extent, have been celebrating his victory.

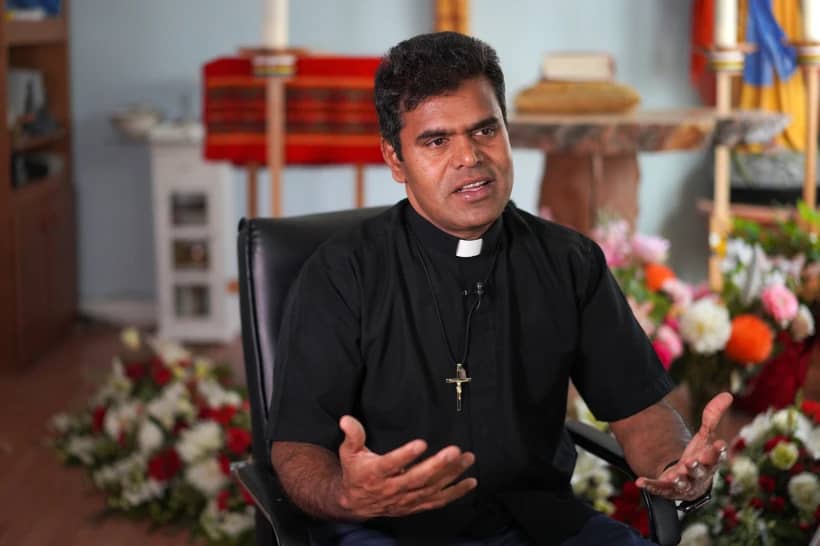

“In the ecclesial world, most people have been seeing it as a signal of democratic progress. Before the elections, some even thought that a coup could be staged and the elections could be suspended,” Father Guillermo Siles, a member of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate and a Church communicator, told Crux.

In the second round, Paz defeated Jorge Quiroga Ramírez, best known as Tuto Quiroga, a right-winger who was Bolivia’s president between 2001-2002. Both of them pledged to break with MAS’s politics, especially when it comes to the current statist economic model.

“There was no place in the campaign for rhetoric involving the defense of social, economic, or cultural rights, nor for the preservation of the plurinational state. All answers came from the right wing,” sociologist Julio Córdova, an expert in the religious dynamics in Bolivia, told Crux.

Much of the country is facing serious shortages of basic items like beef, chicken, and fuel, while there are scarce dollars circulating in the economy – or in the national reserves – and most Bolivians were looking for concrete changes.

“The major demands concerned issues like the high inflation rate, the lack of fuel, and the lack of dollars,” Cordova said.

While Quiroga portrayed himself as a radical neoliberal who would implement immediate changes in the country – at times observers found his rhetoric resembling Argentina’s President Javier Milei’s – Paz “was smart enough to appear as a protector of the informal segment of the economy, which corresponds to 85 percent of the national workforce,” Córdova said.

“Quiroga was clearly the candidate of the agribusiness from Santa Cruz region and talked at times about the need for ‘economic shocks.’ Paz opted to identify with the self-employed workers and to talk about gradual reforms,” he said.

Paz’s moderation clearly pleased the Church more than Quiroga’s radicalism, which he didn’t tone down even in the second round’s campaign.

“Many Catholics voted for Quiroga and believed in his propaganda. He said that Paz would ally with the left-wing and that nothing would really change, but that was a dirty campaign,” Siles said.

If Quiroga had been elected, Siles suspects his radical reforms would have been met with great social pressure, something that “would lead to the repudiation of his policies.”

“That would end up being better for the opposition,” Siles said, adding that he thinks Paz’s gradualism has more chances of being successful.

Paz also declared he will work for everybody, including the opposition, and that he wants more dialogue and less conflict, Siles emphasized.

“Reconciliation was one of the major themes of the statement released by the Bishops’ Conference after the election,” he also said.

In the statement, the Episcopal Conference of Bolivia said that there are great challenges ahead, especially the ones involving the economic reactivation and the needs of the poorest families. But the bishops affirmed they believe the new government will know how to deal with them.

The message included a call for every Bolivian to respect the electoral results and to help to rebuild the country through dialogue, justice and mutual respect.

The Church hierarchy has mostly stayed far from the electoral campaign, Córdova said. Some groups of Evangelical churches have played a much more active role, mostly declaring their support to Quiroga.

One of them was the National Christian Council, which presented a document with central topics for their agenda to both candidates.

“It was a commitment including four items: the defense of life since conception; the defense of family and the repudiation of gender theory; the protection of religious freedom; and the reestablishment of diplomatic relations with Israel,” Córdova said. Only Quiroga agreed to sign it.

Pentecostal segments from Santa Cruz also backed Quiroga. At the same time, other Evangelical groups supported Paz, due to his running mate Edmand Lara’s connections with a number of churches.

“But, in the end, Catholics and Evangelicals voted according to their social class. The lower class tended to support Paz, while the middle classes voted for Quiroga,” Córdova explained.

Rodrigo Paz is a “cultural” Catholic, according to him. He employs Catholic rhetoric at times, but usually avoids combining religion and politics.

Former President Jaime Paz, his father, was a Redemptorist seminarian in his younger days, but was not ordained a priest. Decades ago, he founded a democratic socialist party, of which Rodrigo was also a member. Rodrigo Paz is now a member of the Christian Democracy party.

“He talks very much about family, which is something that gives us the hope that he’ll be open to our concerns,” Siles said.

Most observers think the Church will have much better relations with the new government than it used to have with MAS administrations.

“The Church and MAS have always had conflicts. The declaration of the State’s laicity in 2009, for instance, took the Church out of the forefront during national ceremonies,” Córdova recalled. The Church also lost its primacy when it comes to religious education in schools.

“With Paz, such a mutual distrust will be over. The Church will recover its previous visibility. In some public state institutions, for instance, crucifixes are beginning to reappear,” Córdova said.