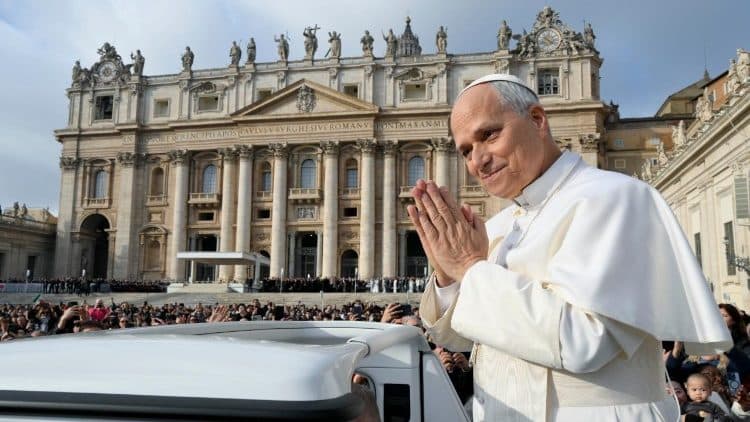

ROME – Pope Leo in his message for next year’s World Day of Peace urged the world to unarm and disarm words and actions – a message that one of his top advisors said goes beyond any contemporary ideology but speaks to what it means to be human.

Asked about the potential role Christian humanism as a political strategy can play in pacifying a world at war and a deeply divided global population, Canadian Cardinal Michael Czerny told journalists Thursday that the pope in promoting peace goes beyond politics.

“One of the strengths of this message is that in fact it doesn’t speak about human-ism, but it speaks to the human,” he said of the pope’s peace message, published Dec. 18 and presented during a press conference that same day.

Czerny spoke at the press conference alongside Bosnian priest and victim of war Father Pero Miličević, and Maria Agnese Moro, daughter of the late Aldo Moro, a former Prime Minister of Italy kidnapped and killed by the Brigate Rosse, “Red Brigades” terrorist group in 1978.

“The expression of peace is not going to be resolved by ideological discussions. That truly, in my opinion, is hopeless,” Czerny told the press, saying Pope Leo’s message to the world when it comes to peacemaking efforts “is that at every level, we need to be truer to our humanity.”

This is something that applies to faithful at the grassroots, but also for leaders in the financial and political sectors, as well as for “the war industry,” he said.

“Nobody can wash their hands. That’s what message says. In that sense, don’t load it off on ‘isms’. Don’t load it off on ‘isms.’ We’re wasting each other’s time with that,” Czerny said, adding, “It’s important for Christians also to recognize that what we have to offer is the human, and not the human-ism.”

An appeal for peace

Pope Leo in his message for the World Day of Peace, titled, “Peace be with you all: Towards an “unarmed and disarming” peace,” issued a lengthy critique of the arms industry, growing investment in defense spending, and the general tendency to invest in armament as a military strategy.

When Jesus appears to his disciples in the upper room after his resurrection saying, “peace be with you,” it is a greeting, he said, that “does not merely desire peace, but truly brings about a lasting transformation in those who receive it, and consequently in all of reality.”

“From the very evening of my election as Bishop of Rome, I have wanted to join my own greeting to this universal proclamation. And I would like to reiterate that this is the peace of the risen Christ – a peace that is unarmed and disarming, humble and persevering,” he said.

He noted that the church has condemned the investment in armament with increased frequency since the Second Vatican Council, saying dialogue has always been “the most effective approach at every level.”

Leo, whose commitment to opening a discussion on the values and risks of artificial intelligence is something he conveyed at the beginning of his papacy, said technological advances and the growing application of AI “have worsened the tragedy of armed conflict.”

To this end, he pointed to a growing trend among political and military leaders “to shirk responsibility, as decisions about life and death are increasingly ‘delegated’ to machines.”

“This marks an unprecedented and destructive betrayal of the legal and philosophical principles of humanism that underlie and safeguard every civilization,” he said, and repeated his frequent condemnation of “the enormous concentrations of private economic and financial interests that are driving States in this direction.”

Pope Leo said peace is often treated like a far-off ideal, noting that war is sometimes “waged in its name” and that increasingly, nations and their leaders “lack those ‘right ideas,’ the well-considered words and the ability to say that peace is near.”

“When peace is not a reality that is lived, cultivated and protected, then aggression spreads into domestic and public life,” he said.

In certain cases, the pope said, it could even be considered “a fault” for some nations “not to be sufficiently prepared for war, not to react to attacks, and not to return violence for violence.”

“Far beyond the principle of legitimate defense, such confrontational logic now dominates global politics, deepening instability and unpredictability day by day,” he said, saying, “It is no coincidence that repeated calls to increase military spending, and the choices that follow, are presented by many government leaders as a justified response to external threats.”

He lamented that global military expenditure increased by 9.4 percent in 2024 as compared to the previous year, confirming a 10-year trend that has now amounted to a total of $2718 billion, or 2.5 percent of global GDP.

Not only has there been an “enormous economic investment” in rearmament, he said, but also lamented a shift in educational policies on peace and deterrence.

Deterrence is not something that ought to be based on “the irrationality of relations between nations” or on fear or forceful domination, but rather on principles of law, justice and trust, the pope said.

“Peace is a principle that guides and defines our choices,” he said, and noted that, “Even in places where only rubble remains, and despair seems inevitable, we still find people who have not forgotten peace.”

“This gift enables us to remember goodness, to recognize it as victorious, to choose it again, and to do so together,” he said.

Pope Leo said the world’s great spiritual and religious traditions have a significant role to play in promoting peace and reconciliation efforts, beyond blood, creed, or ethnicity.

To this end, he criticized the increasing trend to politicize the faith, and “to drag the language of faith into political battles, to bless nationalism, and to justify violence and armed struggle in the name of religion.”

“Believers must actively refute, above all by the witness of their lives, these forms of blasphemy that profane the holy name of God,” he said, urging believers to turn to prayer and dialogue as a path to encounter.

Leo stressed the importance of politicians in pursuing “more humane relations between States throughout the world.”

Mutual trust, sincerity in negotiations, and faithfully fulfilling obligations, he said, are “the disarming path of diplomacy, mediation and international law” that can lead to genuine and lasting treaties.

This process is “too often undermined by the growing violations of hard-won treaties, at a time when what is needed is the strengthening of supranational institutions, not their delegitimization,” he said.

Pope Leo also called for greater investment in justice and human dignity, which he said are at “an alarming risk amid global power imbalances.”

“We need to encourage and support every spiritual, cultural and political initiative that keeps hope alive,” countering a growing sense of fatalism, he said.

Leo closed his message praying that, “May this be one of the fruits of the Jubilee of Hope, which has moved millions of people to rediscover themselves as pilgrims and to begin within themselves that disarmament of heart, mind and life.”

Victims of violence promote peace

Reflecting on the pope’s message of peace, both Miličević and Moro spoke about the violence their families endured, and their own process of reconciliation as indicative of the need to not only pursue peace, but also let go of the desire for vengence and pursue reconciliation.

Miličević spoke of how his life was changed in 1993, when his small Bosnian village was attacked by a unit of Muslim soldiers in Bosnia and Herzegovnia’s army, killing 39 people, including his father, his aunt, and several cousin.

After the attack, Miličević, his mother, and his eight siblings were taken to a camp along with 300 other villagers, where they were imprisoned for seven months before being freed.

“During imprisonment, it was necessary to preserve peace in our hearts and not think of revenge,” he said, saying, “we built peace with him who is our peace” through daily prayer and devotion.

It was many years later, hearing confessions as a priest, that he understood the importance of working for forgiveness, Miličević said, saying peace “must be lived, cultivated and protected.”

He stressed the need to respond to violence with forgivness, and to focus not so much on human justice, which sometimes does not happen, but “eternal justice.”

“We Christians must know that if someone isn’t hit with a human punishment, you can survive with this. I know that war is terrible, I know that many have killed people, even peoples, but our response must be forgiveness…If I hate someone, it doesn’t mark the person who killed my father, my aunt, and many others. But this forgiveness touches me,” he said.

Likewise, Moro reflected on her own process of healing and reconciliation following her father’s abduction and murder, saying peace is not achieved solely by the silencing of weapons.

“We must also defuse the mental and emotional mechanisms that underlie any act of violence, as well as the radioactive waste that irreparable violence, whether committed or suffered, brings with it,” she said.

Moro spoke of the “dehumanization” of violence, saying it becomes possible to attack someone and cause them physical harm only when they are considered “non-human, not like me.”

“Unless you reduce it to a uniform, a function, an enemy, a ghost,” physical harm is not possible, she said, saying, “if you don’t put it aside, you suspend and ignore your own humanity.”

Likewise, those who have suffered violence “by hating those who have harmed dehumanize themselves and the object of their hatred,” she said.

It is possible for humanity to be restored after episodes of violence, she said, but said it comes only after a long process of reflection and awareness, of oneself and what was suffered, but also the other side.

Moro said she underwent this process herself did this 15 years ago, when a friend invited her to participate in a listening session with both perpetrators of the violence of the 1970s and 80s in Italy, including some who were involved in her father’s abduction and murder, and victims of this violence.

“Encountering another’s pain is the first powerful and irreversible blow to dehumanization,” she said, saying, “if you feel pain, you are certainly human, you are like me. We have a language that brings us toghether.”

She said this was the first thing that struck her about those who had been involved in terrorism and who had carried out so much violence.

“I thought the pain was mine, I had never thought of theirs, which I felt all the more intensely because it was never expressed as such, but always in phrases that escaped their lips after being held back for so long,” she said.

To be able to speak to “the other side” after so many years and after so much suffering, she said, was both “painful and beautiful.”

“Every one of my words hurt them, but recognized their humanity. You are capable of listening to me and suffering with me and for me,” she said. Likewise, “their every word hurt me, but recognized my humanity. You are capable of listening to us, of believing in our good intentions from back then, disfigured by the violence used.”

Moro described the moment as one of suffering together in a path of healing and reconciliation, saying, “mutual listening is a recognition of humanity.”

“In this speaking and listening lies all the justice we and they need to live,” she said, adding, “you can hate ghosts forever, but not people. You can’t.”

Czerny voiced his belief that the pope’s peace message also offered a warning to the world to guard against a “false realism” in the sense that violence is someone else’s responsibility, and peace is no longer possible.

“In some ways we’ve been beaten into accepting the logic of war, the logic of armament, the logic of enemies,” he said, saying the pope’s message “doesn’t diminish in any way the horrors that we are surrounded with, it puts an enormous part of the responsibility for it on ourselves.”

“Maybe the first triumph of the logic of war is that we give up our hope for peace,” he said.

To this end, Moro said the pope’s peace message for 2026 is an invitation to focus on reconciliation and the positive steps that have been and are being taken, rather than focusing only on the negative.

“The pope in this message underlines…that in fact, many things have gone forward. There are many places, even among the most activate at this time, in which they give and work to rebuild relations,” she said.

Moro called Pope Leo’s message an invitation “to look not just at the bad, but to look at what is moving, what there is, what goes forward.”

“I think we need it, because we are all a bit drugged by this ‘negative, negative, negative.’ But it’s not like this,” she said, saying, “Each one of us lives in our lives marvelous things also in incredible moments when there shouldn’t be marvelous things, but instead there are…Good is there.”

Follow Elise Ann Allen on X: @eliseannallen