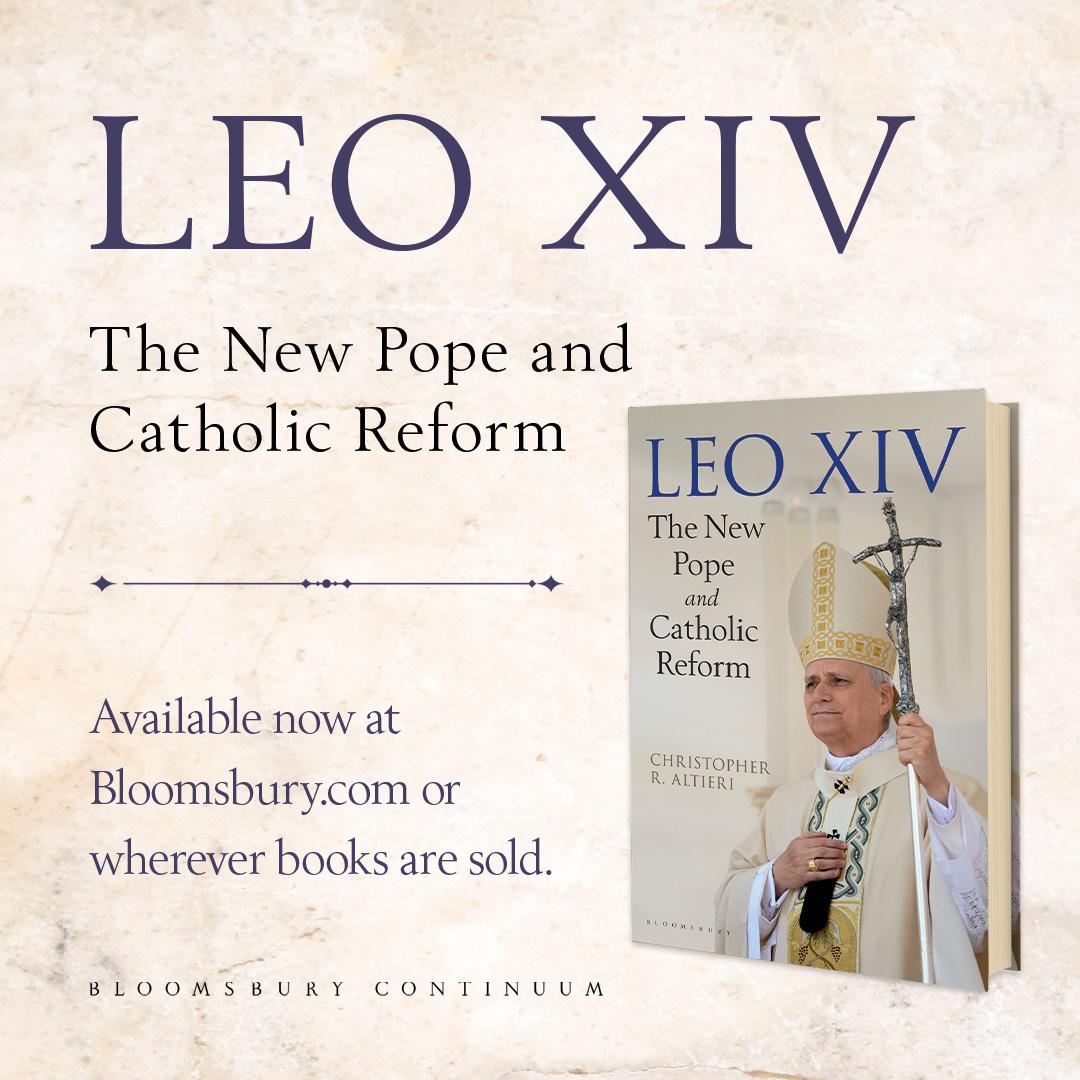

Only a few months after Augustinian Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost was elected to the papacy, taking Leo XIV as his name, Crux’s then-senior editor for news and affairs, Christopher R. Altieri, released Leo XIV: The New Pope and Catholic Reform (224pp. Bloomsbury Continuum, 2025).

I should say from the outset that I was pleased to see myself quoted and cited in the book, but I was deeply moved to discover that the book written by my friend, whom I have known for decades (even before our years together at Vatican Radio), is dedicated to me.

The volume is unique in offering a comprehensive view of the papal office itself, and of the circumstances of the Vatican and of the Church into the global leadership of which Leo XIV has come.

“A provocative and passionate writer, with views forged by decades of experience and a deeply original intelligence,” Crux’s late editor-in-chief, John L. Allen Jr. said of Altieri, who has since become Crux‘s managing editor.

“He’s never been better than he is here,” Allen also said, “especially to be read on the looming challenges of institutional reform – which, as ever, is where the rubber truly meets the road.”

“This is essential reading,” Allen said, “not only on the pope but on the Church in our times.”

The volume has been widely acclaimed in reviews from notable figures and mastheads across the spectrum of opinion in the Church.

I spoke with Altieri – now a professional colleague once again after he began working for Crux – to ask him how he produced so comprehensive a piece of work in such short time. I apologize if our friendship in any way affected our conversation.

Crux: How did this book this book come about, and how were you able to bring it out so quickly following the election of Pope Leo XIV?

Christopher R. Altieri: Dominic Mattos at Bloomsbury Continuum approached me through a mutual friend in May of last year, asking whether I would be able to write something in the way of biography on a very tight production schedule.

To be perfectly frank, I think only our own Elise Allen could have accomplished a proper biography, because only she had the personal knowledge, familiarity with Perú, and institutional contacts to pull off a project like that on such a tight schedule – and boy, did she! – but in the event, I suggested a different project: A book focusing on the papal office itself, on the Vatican, and on the Church as we turn into the middle of the 21st century.

I knew I had useful things to say about all those things, and I felt I was up to the challenge of pulling my thoughts together.

I’ve said elsewhere that I felt not entirely unlike the plumber you call after unsuccessfully attempting to DIY a home repair project. The plumber pokes and tinkers a little, identifies the problem, and solves it, all inside of fifteen minutes.

Then, he sends you a bill for $1,000.

You’re not paying for the plumber’s time. You pay for the years of experience in the trade, which are what made it possible for the plumber to come in and solve your problem in fifteen minutes, flat.

Now, I don’t actually fix anything, and that’s a big difference between me and the plumber.

How has the papal office changed through recent pontificates?

Over the past century or so, especially in the roughly 50 years since the election of Pope St. John Paul II, the papacy has taken on the character of a global office centered in Rome.

For most of history, the papacy had been a local office with universal jurisdiction. I’d love to say more about that, but I’d be giving away the store.

I will also say, however, that one thing I continue to encounter as I present the book to various audiences is a degree of surprise among readers at the extent to which the problems facing the pope and the Church in the 21st century are primarily problems of governance.

I do not think we are used to thinking of the papacy as an office of government.

The three major governance issues with which I deal most closely in the book are daunting reform challenges: Vatican communications, curial culture, and synodality; Vatican finances; and ecclesiastical justice.

These are gargantuan tasks, and they will not be resolved in a day or even in a single pontificate.

Catholics trust in the Lord’s promise to bring the Barque of Peter safely to port. I’m Catholic, and I trust he will make good on his promise, but I also note he makes no promises regarding how well or poorly she will be captained while she is at sea.

Just about the only certainty we have while the ship is underway, is that the seas will be rough.

The election of Prevost took a great many Vatican watchers by surprise, including you. In the book, you talk about how the choice made perfect sense, in hindsight: How did you miss it?

In the book, I talk about my real-time reaction to hearing his name. “Robert … Francis … ?” I thought. “That’s Prevost!”

I was live-to-air and I recall – when the producer cut away from me – saying something like, “I know who he is!”

In fairness to everyone who discounted him, though, the man who became Leo XIV gave himself impossible odds heading into the conclave, too, and for much the same reason those of us who had discounted him had done so: I just did not think the cardinals would elect anyone from the US.

It didn’t take long for me to realize, however, how well he fit the profile of the man for whom I knew the cardinals would be looking: An institutionalist who isn’t a cog in the Roman machine; someone with knowledge of the Church’s international role and global footprint who is not a career diplomat; someone capable of holding an audience in several languages but not a fellow who craves the limelight; someone who would be willing to stay home and govern the Church; someone whose leadership record on clerical abuse and coverup had already been vetted to some extent, at least, and could sustain almost immediate and searing public scrutiny.

Leo XIV had weathered a couple of major storms when he was still Cardinal Prevost. Crux had a hand in reporting them.

Still, all that comes to a very tall order, and it continues to be remarkable how well the man we call Leo XIV fits the bill.

It also very quickly became clear to me how his Augustinian spiritual formation and his global leadership experience in his Order of Saint Augustine also contributed to his profile, as did his training and experience as a canon lawyer.

For what it’s worth, I think the 10 months we’ve had with him so far have borne all that out.

If I had to pick one key to understanding how he intends to conduct the office, it would have to be his thoroughly Augustinian cast of mind. It informs his anthropology – his thinking about human nature – something already evident in his speeches and homilies.

It is also evident that he has a thoroughly Augustinian sense of history. For St. Augustine of Hippo, history is a mode of consciousness, an attitude of the soul that becomes an aptitude of the spirit when it is infused with the theological virtue of hope.

Leo XIV has already talked a great deal about the challenges posed by the rise of artificial intelligence. Do you see this continuing to be a major theme of his teaching pontificate?

I’ll go at least one further and say it will be one of the measures by which the success or failure of his pontificate will be gauged.

We are experiencing – in real time – a kind and degree and extent of social and civilizational disruption not seen since the industrial revolution of the 19th century. Leo has said he took his name in acknowledgment of this reality, harking back to Leo XIII, who gave the Church and the world the first major social teaching document of the modern industrial era.

The other Leo his choice recalls is the first pope of that name, Leo the Great, who reigned in the waning days of Roman imperial power in the West.

I have already written about this for Crux, and – it goes without saying – there is much more about it in the book, but I think we have already seen Leo working to leverage what Pope St. Paul VI called the Church’s “expert[ise] in humanity.”

I think we will see him continue to retrieve and present the profound and perennially valid anthropological insight the Church carries in her vast storehouse of wisdom, and we will see him bring that expertise to bear on the times.

If anyone can retrieve a coherent notion of nature – particularly human nature – in the face of a 21st century technological eclipse, and articulate it in accessible terms, it will be an Augustinian.